With health and well-being an increasingly important consideration in towns and cities, Yvonne Rydin and Helen Pineo discuss how surveyors can contribute to healthier lives.

While high-income and low-to-middle-income countries face very different health and well-being problems – with issues of clean water and sanitation pressing for the latter group – there are a range of shared priorities. These include the lack of opportunities for physical activity in daily life; noise and air pollution; limited access to affordable housing; ill-preparedness for the impacts of climate change; poor thermal comfort and air quality inside buildings; restricted access to green spaces; the importance of designing for groups with special needs such as children, the elderly and disabled people; and the value of learning from communities about their perceptions of health and place.

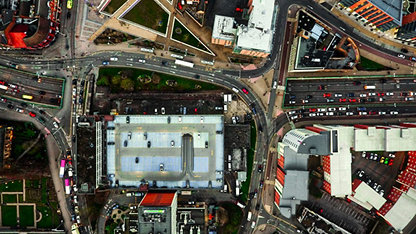

The first important point is that much of the work of surveyors has implications for health and well-being in our towns and cities. The design, development and management of the built environment can contribute to better health in a variety of ways:

- it can reduce pollution of all kinds – such as airborne pollutants and noise – both indoors and outdoors

- active transport – cycling and walking – can be promoted and the conditions for use of public transport fostered, rather than reinforcing reliance on the car

- better land-use mix in and connectivity across urban developments can become a way to generate a sense of local community

- green spaces and parks can be incorporated, bringing physical and mental benefits, while the associated greenery and water features can combat the urban heat island effect that exacerbates the impact of heatwaves in cities

- incorporating elements of urban agriculture may tackle problems of access to fresh fruit and vegetables and promote better diets.

Almost all the elements of a development proposal and management plan can be interrogated for their potential contribution to improved health and well-being. There are many cases where an alteration will even bring multiple benefits, as with the creation of pedestrianised, landscaped areas at the heart of new developments, which encourage walking and sociability, provide shade during heatwaves, allow moments of peaceful reflection, and minimise the impact of polluting road vehicles.

In tandem: two cities putting bikes first

In the pink in Auckland

The “Te Ara I Whiti” cycleway in the New Zealand capital, Auckland, replaced a freeway slip road and is wide, pink and studded with Maori symbols. It joins up with three existing cycleways, with plans for another to link in soon. Experts cite this sort of approach as the most effective way to go Dutch.

Seville in the saddle

“Now in fabulous Seville on a visit to see how the city was transformed into a major cycling and walking city,” tweeted British transport minister Jesse Norman in January. Between 2006 and 2010, the Spanish city created a 75-mile network of cycleways, which led to an elevenfold increase in cycling.

Design for health

But it is not just that surveyors could contribute in theory: there are also compelling reasons why they ought to do so. For instance, there is increasing evidence – particularly among prime property – that the incorporation of features contributing to health and well-being also brings a financial return in terms of rental and capital values.

One specific means by which this link is created is the way that productivity in office environments is boosted by features such as views of greenery, use of natural materials and natural light and ventilation. Property owners and tenants alike are increasingly recognising the benefits of design for health and well-being and this is influencing market prices and rents.

Ensuring that a development or building meets high standards of design, construction and management for health and well-being is also relatively easy. Indeed, well-established building and development standards such as BREEAM and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) already incorporate criteria to assess this.

Healthier standards

The RICS Cities, Health and Well-being insight paper compared these standards with the WELL Building Standard and found that more than a third of the issues covered in the latter were already present in BREEAM and LEED. The main deficiencies in the broader standards were in issues concerned with water, nourishment and mental well-being.

If a developer, investor or occupier wishes to move beyond these well-established criteria for buildings, then, they could consider adopting the WELL or Fitwel standards. Using such standards not only demonstrates commitment to health and well-being but also provides a structured means of ensuring that the different dimensions of this agenda are taken on board.

“The creation of pedestrianised, landscaped areas at the heart of new developments, encourage walking and sociability, provide shade during heatwaves and minimise the impact of polluting road vehicles.”

At the broader scale of neighbourhoods or local authorities, there is also scope for using Health Impact Assessments to consider how plans, policy and strategies might affect health and well-being and the extent to which this agenda is being adopted. Mirroring systems such as Environmental Assessment, these are generic methods for systematically considering the impacts on health and well-being of proposed urban development pathways. The advantage is that the earlier that health and well-being are incorporated into the planning of a locality, the easier it will be to achieve beneficial outcomes and avoid incurring costs. New facilities such as transport networks, energy supplies, water and green infrastructure can all be more readily integrated at an early stage of planning, and this can then guide specific development and building projects.

Positive projects

The insight paper highlights some recent development projects in France, the USA, Singapore and the UK at multiple scales that have incorporated health-promoting design features. For example, the Paya Lebar Quarter is a Lendlease development in Singapore that integrates sustainability and health features. The project includes three office towers, a retail mall and three residential towers with 429 apartments, surrounded by public space, and aims to provide trees, green walls and roofs and urban farming to reduce the urban heat island effect, support biodiversity, manage rainwater and encourage community gardening. The project also includes plans for active transport, social interaction, indoor air-quality improvements and biophilic design. The three office towers are registered for the WELL Core & Shell Certification, which they aim to fulfil with, for instance, the provision of showers, lockers and bicycle storage facilities.

On a smaller scale, the insight paper also provides many examples of health-promoting design in buildings or at street scale. For example, offices and public buildings may encourage occupants to be more physically active by ensuring that stairs are visible and providing sit–stand or treadmill desks. In London, Southwark Council’s Tooley Street office and the NHS Health Education England office have signage encouraging the use of stairs, with the former providing details on calories burned per floor, and the latter using playful art to remind occupiers of the benefits of climbing stairs rather than using the lift.

Six steps to healthier projects

-

This may involve gathering and consulting public health evidence, looking at employer’s survey data and engaging with residents and other occupants, giving a new perspective on the way public health is important to your clients.

-

This involves thinking about how design standards could meet different needs in a building and development; vulnerability in this case may relate to age, physical or mental health and other disabilities.

-

There may be a variety of ways in which changes to the details of a development can enhance health and well-being. Incorporating them early on during the planning and design process can make them easier to adopt and will reduce costs. There may also be benefits for other objectives such as energy efficiency.

-

It is always important to remember the financial implications, but many ways of contributing to health and well-being are cost-neutral or can be achieved with a short payback period. Demonstrating this will reassure clients that they are making a worthwhile investment.

-

Such standards are already part of normal business practice in urban development, and adopting a standard with a clear health and well-being perspective is a simple way of taking the public health agenda on board.

-

Maintaining a record of how contributions to health and well-being have been achieved, their costs and their benefits can help build the case for further engagement with the public health agenda.

- This article was first published in RICS Land Journal (Oct/Nov 2018)

Yvonne Rydin is Professor of Planning, Environment and Public Policy at the Bartlett School of Planning, University College London.

Helen Pineo is Associate Director, Cities at BRE, and from September 2018 is joining the Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment at University College London as a Lecturer in Sustainable and Healthy Built Environments.