How quickly can a total transformation of the energy system be achieved? In the first of this three-part series, Langdon Morris, leader and senior partner, InnovationLabs and Farah Naz, director of ESG and innovation, Middle East and Africa, AECOM, explore the historical, moral and ethical aspects of achieving net zero through the energy transition.

This article is the first of three excerpts from the book Net Zero City by Langdon Morris and Farah Naz.

Modern civilization, as experienced through the contemporary global economy, requires huge quantities of energy to facilitate all aspects of modern life. For the last two hundred years, fossil fuels in many forms have been abundant and abundantly used to meet this increasing need. Global spending on energy in 2020 totalled a tidy US$ 6.3 trillion, and about 83% of the total energy consumed was from fossil fuels.

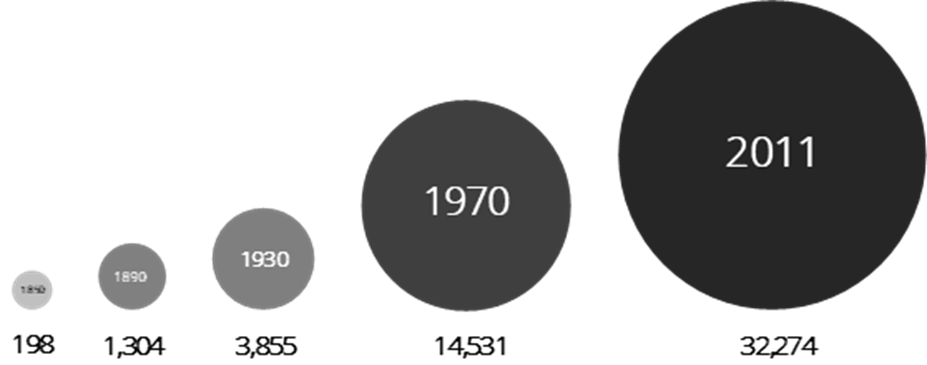

Global emissions of CO2 have also increased sharply. From nearly nothing in 1750, emissions increased to about 6 billion tons of CO2 by 1950, and then leaped in the second half of the century to reach about 30 billion tons by 2000, and now is about 36 billion tons of CO2 each year.

The British Petroleum report for 2019 shows that fossil fuel consumption of nearly 600 exajoules resulted in the release of 34 billion metric tons of CO2 (which is 74 quadrillion pounds, or 7.4 x e13), and now that climate change is having a major impact, it’s evident that we are obliged to shift away from their use and adopt other sources for the energy we require. This shift, widely known as the ‘energy transition,’ is now under way.

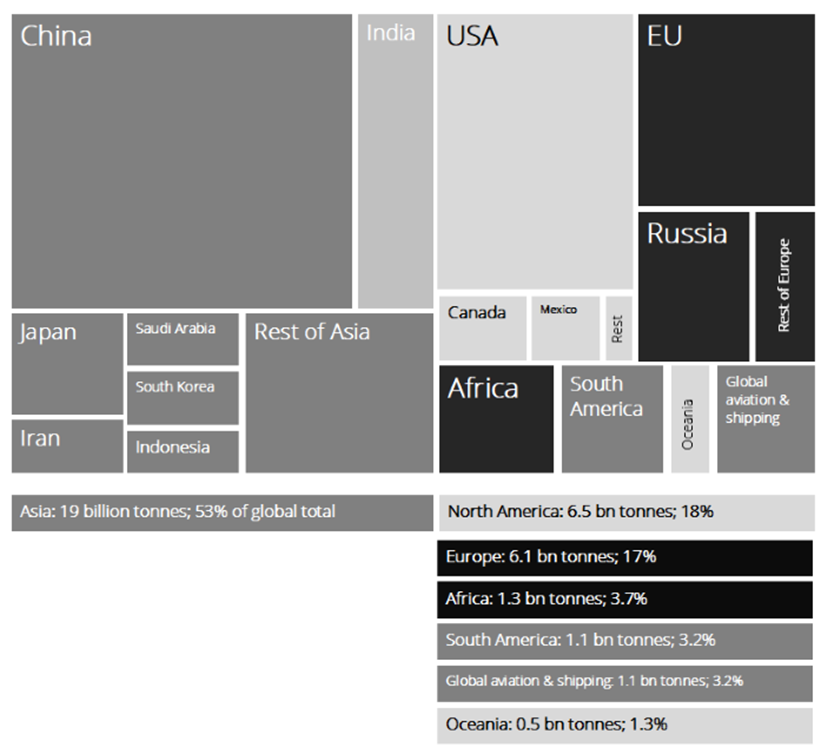

Figure 1: CO2 emissions by nation & continent. (Source: Author’s own figure using data from Global Carbon Project & OurWorldinData.org).

Defining a ten-year net zero transformation journey

At the beginning of the 20th century, more than 90% of global emissions came primarily from Europe and the United States, but as the century progressed and Asia’s economies developed, Asian nations have come to emit about 53% of the world’s total, of which 27% comes from China.

The International Energy Agency, a nongovernmental organization focused on assuring energy security, was established in 1974 to help design a response to the OPEC Oil Crisis. The title of its 2021 report, Net Zero by 2050, quite clearly describes its revised objective, to leave the oil industry entirely and reinvent a sustainable energy foundation for society.

Indeed, in its 227-page report, the IEA calls for ‘a total transformation of the energy systems that underpin our economies’. Its warning is clear, telling us that 2021 is the ‘critical year at the start of a critical decade for these efforts,’ which must start turning the world’s Business As Usual energy system dominated by fossil fuels into a future ‘powered predominantly by Clean Technology, and mostly renewable energy such as solar and wind’. The report also presents a roadmap consisting of more than 400 milestones showing how this transformation should happen over the next 30 years, including an immediate call for action to end new investment in fossil-fuel extraction towards achieving net-zero electrification by 2040.

This passage offers a quite pointed statement of need:

‘We are approaching a decisive moment for international efforts to tackle the climate crisis – a great challenge of our times. The number of countries that have pledged to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century or soon after continues to grow, but so do greenhouse gas emissions. This gap between rhetoric and action needs to close if we are to have a chance of reaching net zero by 2050 and limiting the rise in global temperatures to 1.5˚C. Doing so requires nothing short of a total transformation of the energy systems that underpin our economies.’

While the overall message is compelling, we have concerns that the 2050 target date may be too far in the future, as by then it will likely be too late to avert global disaster. Climate scientists are clear that we should be targeting Net Zero earlier than 2050, so our focus here is on defining a Ten Year Net Zero Transformation journey, 2022–2032.

Whichever target date you pick, there’s no question about the need for a total transformation of the global energy system, and thus IEA’s action prescription calls for ‘…vast amounts of investment, innovation, skillful policy design and implementation, technology deployment, infrastructure building, and international co-operation’.

Energy in the modern world – history and transitions

Prior to about 1800, the vast majority of energy applied throughout the world was from humans, animals, water, and wood, but with the development of industrialized machines powered by coal, the world undertook the transition from muscle to coal. In the 20th century we made another transition, shifting primarily to oil and its derivatives for transportation, and later to natural gas for electricity generation. The side effect, of course, is the massive increase in CO2 emissions.

While in mid-century many people expected nuclear power to become the fuel of the future, fossil fuels still remain predominant well into the 21st century.

Figure 2: Global carbon dioxide emissions, 1850 – 2011; Million metric tonnes of CO2; 2011 emissions are 163 x 1850 emissions. (Source: Author’s own figure, using data from World Resources Institute; ClimateWatch).

But with the accumulation of increasing tons of fossil fuel’s greenhouse gas wastes in the atmosphere, we can foresee a much different energy mix for the future, with significant reliance on wind and solar. But how soon is that future?

The IEA Report notes that,

‘The path to net zero requires immediate and massive deployment of all available clean and efficient energy technologies, and scaling up solar and wind rapidly this decade. Annual additions of 630 gigawatts of solar and 390 gigawatts of wind by 2030 are needed, four times the record levels set in 2020’.

This will be a significant acceleration from the historical norms, as the transition from one predominant fuel to the next one has in the past required many decades to complete. This is largely because the infrastructure required to make use of any given energy source is massive, extensive, hugely expensive to install, and thus highly difficult to replicate.

For comparison, energy scientist Vaclav Smil estimates that the existing fossil fuel infrastructure supplying building and transportation needs totals an investment of more than $20 trillion in the US alone, and it took more than 100 years to build it. Even with all the intention in the world, and an unlimited budget, it may still take decades to replace this infrastructure with a comparable infrastructure to capture and deliver sustainable energy.

But this is exactly the effort that humanity has now begun to undertake.

The moral, ethical, and accountability aspects of energy

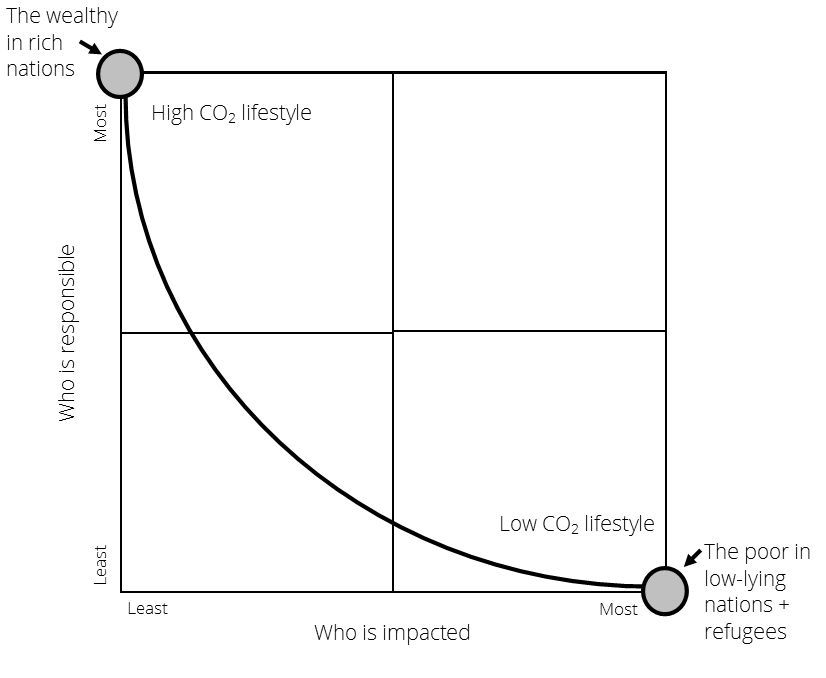

There is a compelling moral and ethical aspect of the energy transition, as on both a local and global basis, it’s clear that those who will be most severely impacted by climate change will be those least able to afford the costs. It is the poor people and small nations that will suffer most.

But they’re also, in a sad irony, the ones who are least responsible for the overproduction of greenhouse gases, since the wealthy nations produce the vast majority of CO2 emissions.

For example, the small Pacific and Indian Ocean island nations such as The Maldives (population 530,000) and Tuvalu (population 11,600) contribute next to nothing of the globe’s annual greenhouse gas production, but they’re the nations most likely to be submerged, turning all their citizens into refugees.

Consequently, Vaclav Smil also notes that, ‘Shaping the future energy use in the affluent world is primarily a moral issue, not a technical or economic matter’. Smil adds that the cost to protect a great deal of the Earth’s existing biodiversity in year 2000 would have been around US$ 26 billion per year, or roughly the amount spent that year on cinema tickets.

This disparity defines an important moral responsibility for leaders and for citizens, as the wealthy and privileged must make what may be difficult challenges and changes to their lifestyles, and to accept the costs of transformation, in order to lessen the burdens on the climate, and on the poor.

This will, of course be particularly challenging for nations that are high-volume producers and users of fossil fuels, which include many in the Middle East, and also the US, China, Australia, and Norway, among others, as it will result in multiple levels of economic impacts. Nevertheless, industry is making progress.