Is it time our town centres found a new purpose and stopped fighting their losing battle against online retail? Built environment journalist Mark Smulian investigates.

Can there be any purpose in “defending” something once its economic purpose fades? The obvious answer is “no”, but still talk persists about defending the traditional high street while the growth of online and out-of-town retailing hollows it out.

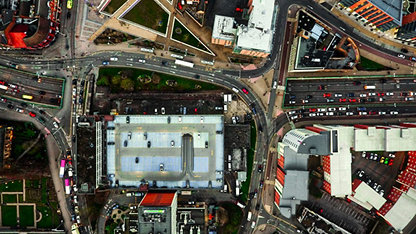

For planners and the property industry, the idea of a town centre no longer being the focus of retail and commercial activity demands some careful reassessment, as does the challenge of sustaining “retail-led” regeneration – a staple of pre-crash urban renewal.

It might, for example, involve planning for residential, leisure, education and healthcare where shops once stood, creating a town centre that people still visit but only incidentally for retail.

Famous UK retail names that have vanished in the past year include Toys R Us, Maplin and Poundworld. HMV is on the brink. The Centre for Retail Research reports that 43 retailers bit the dust in 2018, affecting 2,594 stores: more than the total for 2016 and 2017 combined. Furthermore, research by Paul Michael Greenhalgh, professor of real estate and regeneration at Northumbria University, found that between 2008 and 2015, total retail floorspace shrank in all but five local authorities in England and Wales, from 1.69bn ft2 (157m m2) to 1.23bn ft2 (114m m2).

The UK’s love of online still makes it an outlier compared with many other developed countries, but the direction of travel is only going one way. E-commerce sales represent 18% of the UK market – and 25% of all fashion sales – and are predicted to grow at a faster rate (15%) than other Western European countries between 2017 and 2021.

High streets have clung on against the internet onslaught through shops that provide personal services or items that are required immediately – hairdressers, coffee bars and convenience stores, for example – but those alone cannot sustain a town centre. Planners must seek solutions to keep these spaces vibrant and prevent them becoming decrepit once declining retail brings empty premises. In the battle for the soul of the high street, the best form of defence is to adapt.

Former Iceland chief executive Bill Grimsey, who has conducted two reviews for the government on the state of the UK high street, says: “Plans for town centres have to change. The key is community, not retail, and it’s a broader issue than shops. Forget retail dependency and instead encourage local authorities to plan unique places to live, work, play and shop, prioritising health, education, eating out, leisure and housing. It’s useless to resist [change], as by 2030 about 30% of all shopping will be online. The whole argument that town centres can be fixed with shops is flawed,” he says.

“Some high streets are doing fine, but for others it’s an ugly tale of no longer being fit for purpose when the world has moved on around them.”

Stephen Springham , Head of retail research

Knight Frank

There are alternatives if you apply some lateral thinking, Grimsey adds: “Town centres can do other things. Younger people spend a lot of time in cyberspace but could be invited to bring their devices to events. We are social animals and want to meet each other, and town centres can provide that. People [would still be] coming in, and might also buy things; we just won’t need as many shops.”

One place that applied similar thinking is Kingston upon Hull, says the city’s planning manager, Alex Codd. The council fought off an application for a large out-of-town retail project by showing that the city centre had sufficient sites for any additional retailing.

Even so, Codd says: “People no longer come to the city centre just for retail, they’re looking for more of an experience.

“Some local authorities say it’s terrible that you can have a shop or office changed easily to residential use, but if you’ve got under-used space, why not change it? We are getting residential into the city centre, too.”

Codd adds: “What helped was that we had already invested in £26m of public realm improvements and a new square adjacent to the retail sites. You have to diversify what you have in a city centre.” Hull spent 2017 as UK City of Culture, for which it revamped its art gallery and theatre, opened a new live music venue and created a dining out area.

Hull is helped by having no competing urban centre nearby, but some former industrial areas in close proximity to each other face greater difficulty (see case study). “One shouldn’t generalise, as some high streets are doing fine, but for others it’s an ugly tale of no longer being fit for purpose when the world has moved on around them,” says Stephen Springham, partner and head of retail research at Knight Frank. “It’s a particular problem in older industrial towns where the population has declined over, say, 50 years and there is surplus floorspace.”

Springham is suspicious of calls to simply convert this to residential to fix the UK’s mismatch of a housing shortage with its excess of shops. “Generally, the places where there is a major shortage of residential are not the ones with declining retail and I’d question whether those conversions would stack up financially,” he says. “But you could see a range of residential working in town centres, including students, social housing and retirement housing.”

Rebecca McDonald is an analyst at the Centre for Cities thinktank, who co-wrote its June 2018 report Building Blocks: The Role of Commercial Space in Local Industrial Strategies. She argues that the best performing high streets are those in places with a high proportion of “exporting” businesses that sell goods and services elsewhere. These businesses could locate anywhere but choose places with a good supply of skilled labour and the type of public amenities that attract them. Their employees tend to be better paid and, consequently, spend more money in their local town centre.

Centres dominated by businesses that are solely dependent on local custom, by contrast, rarely do well. And whereas “strong” exporting cities have a mix containing more than 50% offices (graphic, opposite), McDonald says, “‘weak’ city centres have more than 50% retail space, which makes them much more vulnerable to closures. The private sector has no incentive for investing in repurposing this retail space because the rents are so low, which means local authorities will need to intervene.”

According to Centre for Cities, among the options that councils should consider are: intervening to supply small amounts of new office space for more export-based businesses; converting the excess supply of shops into residential and office uses or, where demand for this type of property is low, demolitions to return the land to the public realm; and reforming business rates to finance interventions into commercial space in “weak” cities.

If the future high street is a mix of residential, leisure, education, health and what remains of retail, then a move away from traditional thinking to a more flexible approach to planning use classes is required. Even 10 years ago, online shopping was still rare. The problem for planners is that they now have to think about the long-term for high streets as the economies that have sustained them for a century shift quickly in unpredictable ways.

- Mark Smulian is a highly experienced built environment journalist.

This article originally appeared in The Cash Issue of Modus (March 2019), titled Everything Must Go.