There are few images of urban decay as striking as that of Detroit. At one time the midwestern city defined American mass market capitalism as the centre of the auto industry.

But when Ford, General Motors and other great auto brands lost their dominance, “Motor City” began a downward spiral that featured a population flight from the centre to the suburbs. The hollowing out of Detroit’s centre resulted in a landscape now littered with gutted, once-grand buildings.

Detroit’s experience is not unique. Many other rust-belt cities in the US, including the former “Steel City” of Pittsburgh and manufacturing centre Cleveland, are losing residents, in contrast to a global trend of rising urban populations around the world. Even capital cities such as Copenhagen and Madrid are having to face the challenge of shrinking populations by finding ways to develop their centres.

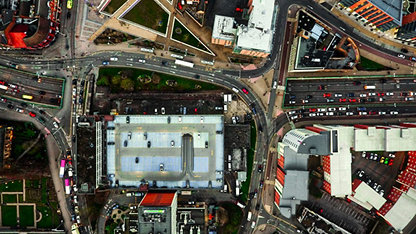

Sameh Wahba, the World Bank’s director for urban and territorial development, disaster risk management and resilience, says there are plenty of consistent features that characterise shrinking cities. And while it might be economic decline that triggers an initial decrease in tax revenues that limits the ability to deliver good-quality services, other factors then come into play. “When you have roads that are getting less maintained and health and education services that are declining in quality, it may result in a flight to the suburbs or relocation to other places,” says Wahba. “The second challenge is the inability to manage negative externalities such as congestion and pollution.”

“A common thread the world over is the need to implement a joined-up planning perspective by looking at solutions such as connectivity, pollution, congestion and sustaining service delivery”

Wahba says many of these factors are faced by fast growing cities such as Beijing and Delhi. But, he adds, the vicious circles that are allowed to develop without effective interventions can then result in shrinking cities. “If authorities are unable to deliver public transportation services, or unable to manage congestion on the road network, [then] people are taking more time to get to their jobs, resulting in a loss of productivity.

“There’s also significantly reduced liveability that comes with increased air pollution, often the result of an inability to invest in better transportation or make an intervention in energy generation, or in other areas such as agriculture and burning of waste. So, these would be examples of decline where you find cities are unable to generate tax and non-tax revenues – and ultimately of failed service delivery.”

A common thread the world over is the need to implement a joined-up planning perspective by looking at solutions such as connectivity, pollution, congestion and sustaining service delivery, says Wahba. But the starting point is finding the means to reconstruct the city centres and plugging the financial gap left by tax revenue shortfalls to deliver services and create a virtuous circle for regenerating the city.

Rejuvenated cities: Seoul

From 1975 to 1995, Seoul’s city centre experienced a significant decrease in residential and commercial activity, where small plots, narrow roads and high land prices made development too costly. So, the city launched a revitalisation project to redevelop an 18-lane elevated highway into 40 acres of green public space, dramatically increasing real estate values and the variety of uses for the downtown areas.

Downtown Detroit was a classic example of a city requiring a turnaround based on addressing these fundamentals. “Lack of economic diversity resulted in a massive loss of jobs when the fortunes of the automobile industry changed,” Wahba explains. “A sudden depopulation of the city and a flight to the suburbs meant the inner city of Detroit has had a shrinking population and significant declining tax base, from property taxation and corporate taxation, resulting in the city being put into administration.”

Rebuilding Detroit involved using all the means at the city’s disposal, including vast tracts of possessed land that could be repurposed and would be attractive to investors, and a city administration that was prepared to pull out all the stops to succeed.

Under the leadership of mayor Mike Duggan, Detroit’s planners employed a model used across the world to reinvigorate cities, most notably Singapore: that of using an anchor investor. “You do whatever it takes to get the first investor on board, and then other investors and developers will come with more competitive requests and proposals because you’ve started the regeneration,” says Wahba.

Detroit was a successful outcome that followed this formula, says Ellen Dunham-Jones, professor at the School of Architecture at the Georgia Institute of Technology. She says that despite the fact that reversing the vicious cycle is often an extremely hard task, Motor City had some ace cards to play: “Detroit was able to leverage then-dirt-cheap housing and commercial space costs to attract young, hip entrepreneurs – alongside having an angel investor, [Quicken Loans founder and Detroit native] Dan Gilbert, who was prepared to invest in downtown and bring in good jobs.”

A slightly different approach was taken by Pittsburgh, the great steel city to the east, where revitalisation took a more conventional path – investing in stadiums and cultural venues, and redeveloping the old steel mills that once dominated the skyline into mixed-use entertainment and shopping destinations, while investing in transit. “Crucially, both made their downtown destinations for their regional populations again,” adds Dunham-Jones.

Both Detroit and Pittsburgh can claim success in their efforts at urban renewal and halting the shrinking populations at their cores, says Dunham-Jones, who suggests an element of luck and good timing may have also played a part. “The regeneration and revitalisation of downtown Pittsburgh and Detroit hit the market just as urban living has been enjoying widespread appeal in the US.

“What differentiates them from other downtowns in the south and west that have seen a resurgence is that Detroit and Pittsburgh are also both ‘legacy cities’,” she adds. “Their industrial legacy produced great wealth in a number of families, family foundations and new businesses that have been able to fund the planning and catalytic projects that helped their revitalisation.”

Rejuvenated cities: Buenos Aires

As Buenos Aires’ urban sprawl moved away from the city centre, it left swathes of prime waterfront land with significant architectural and industrial heritage vacant and underused. To tackle the problem, the city used a self-financing urban regeneration initiative in Puerto Madero to redevelop 420 acres into an attractive mixed-use waterfront neighbourhood. The investment totalled $1.7bn, $300m of which was raised through the sale of land.

How far both have come is best judged by direct experience rather than hard numbers. Dunham-Jones encountered two different cities when visiting. “I was quite stunned on my most recent visit to Detroit, in 2016, at how vibrant and full of people the downtown was at 3am on a Saturday night. My last visit to downtown Pittsburgh was in 2014 and while it was quite lively during the day, I didn’t see anything like the nightlife I saw in Detroit. My guess is there aren’t enough residents yet in either downtown – but Detroit seemed to be better at attracting young entrepreneurs,” she notes.

But these cities are a world away from other metropolises that have failed to regenerate with anything like the same degree of success. Take Youngstown in Ohio, another former steel-producing city that several years ago chose to try to “re-green” and encourage the remaining households in largely vacant neighbourhoods to move into those that still had clusters of population.

“The plan was to shrink the urban service areas and return vacant neighbourhoods to farming or park land,” says Dunham-Jones. “Detroit proposed a similar plan about the same time but while both cities received a great deal of backlash – that it was too pessimistic, that it was erasing a still-living culture – Detroit has since, via Gilbert’s investments, focused on its downtown and is now working with residents in largely vacant neighbourhoods to incrementally renovate homes. While Detroit has had a lot of well-deserved press, I haven’t heard about anything happening in Youngstown.”

Even when there are clear signs of early renewal of one shrinking city centre, there are question marks over the degree of sustainability of a project, argues Professor Ronald Wall, head of urban competitiveness and resilience at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

Wall cites Johannesburg’s CBD as an example of where the envisaged formal growth and renewal has not yet taken place, but where a more informal and erratic growth has emerged in precincts such as Maboneng and Braamfontein. “Maboneng district in downtown Johannesburg is similar to the Docklands in London, as it concerns an old industrial part of the inner city that has been revitalised. But unlike Docklands, which was developed through local government, Maboneng was a private initiative.

“The area is today a successful cultural and tourist destination. However, it is debatable whether the Maboneng project is a successful and sustainable urban regeneration model, as there are underlying socio-economic, racial and governmental issues that make it unsustainable and unattractive. Regeneration projects often tend to create outplacement and exclusion,” says Wall.

His comments are a reminder that the challenge of regenerating cities, especially shrinking metropolises, is a long and complex process. Successful cities need to raise their offer in an ever more competitive global environment and, as Wahba observes: “Usually cities have succeeded in becoming more competitive only when they become more liveable.”

- Lawrie Holmes is a journalist and editor working on titles such as CEO magazine, CIMA’s Financial Management, CIM’s Catalyst, UKTI’s Springboard and EY’s Reporting.