India’s property sector has outperformed global trends over recent years – but can it maintain this momentum? The second of two articles examines the data.

Authors

Donglai Luo, RICS economist

Vivek Rathi, head of research, Knight Frank India

Shilpa Shree, assistant vice president – research, Knight Frank India

Despite a downturn in real-estate markets around the globe, India’s property sector continues to perform relatively strongly. The country’s economic growth has been resilient, despite interest rate hikes made with the aim of managing accelerating inflation.

Alongside increased external demand and robust foreign direct investment, India’s attractiveness as a service hub has led its economy to recover relatively quickly from global headwinds in the past few years. But does the data indicate that this performance can be sustained?

Private sector momentum drives construction

Besides the boost from external demand, a key characteristic of the upturn in the Indian building industry is the optimism in the private sector.

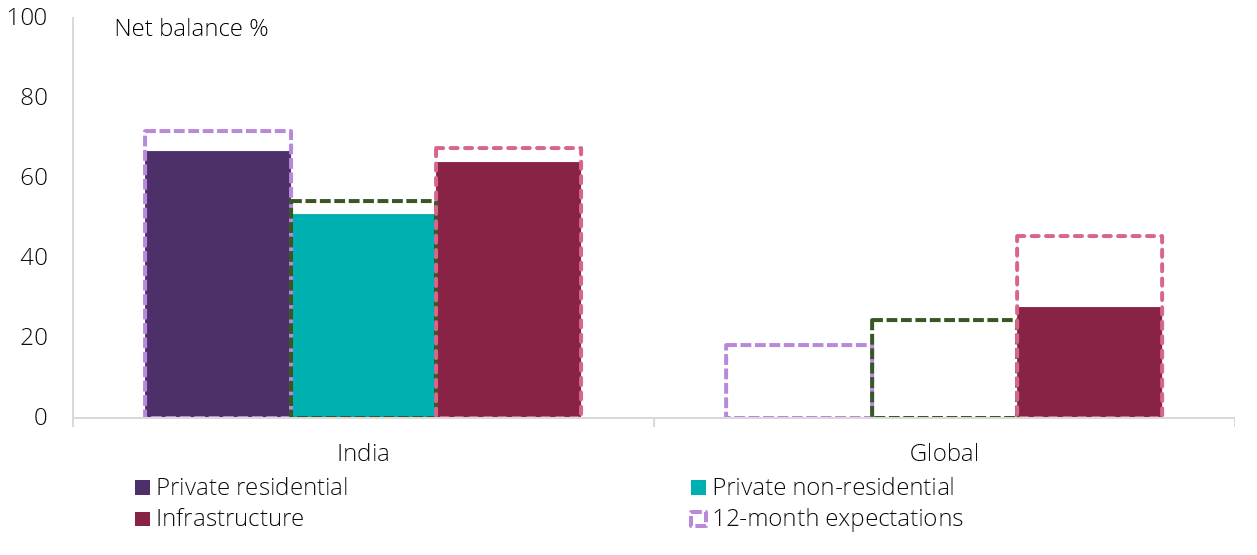

Figures from the latest RICS Global Construction Monitor (Figure 1) reflect a positive outlook for workloads across residential and non-residential property, with the performance of and outlook for subsectors in India significantly surpassing the global average. Moreover, these statistics indicate a more balanced distribution across the various subsectors than the global average, which is skewed towards infrastructure.

On a longer time horizon, similar optimism is also reflected from Oxford Economics’ 12-month forecasts across subsectors, which indicate that India's construction industry will experience an average annual growth rate of 6% in gross value added.

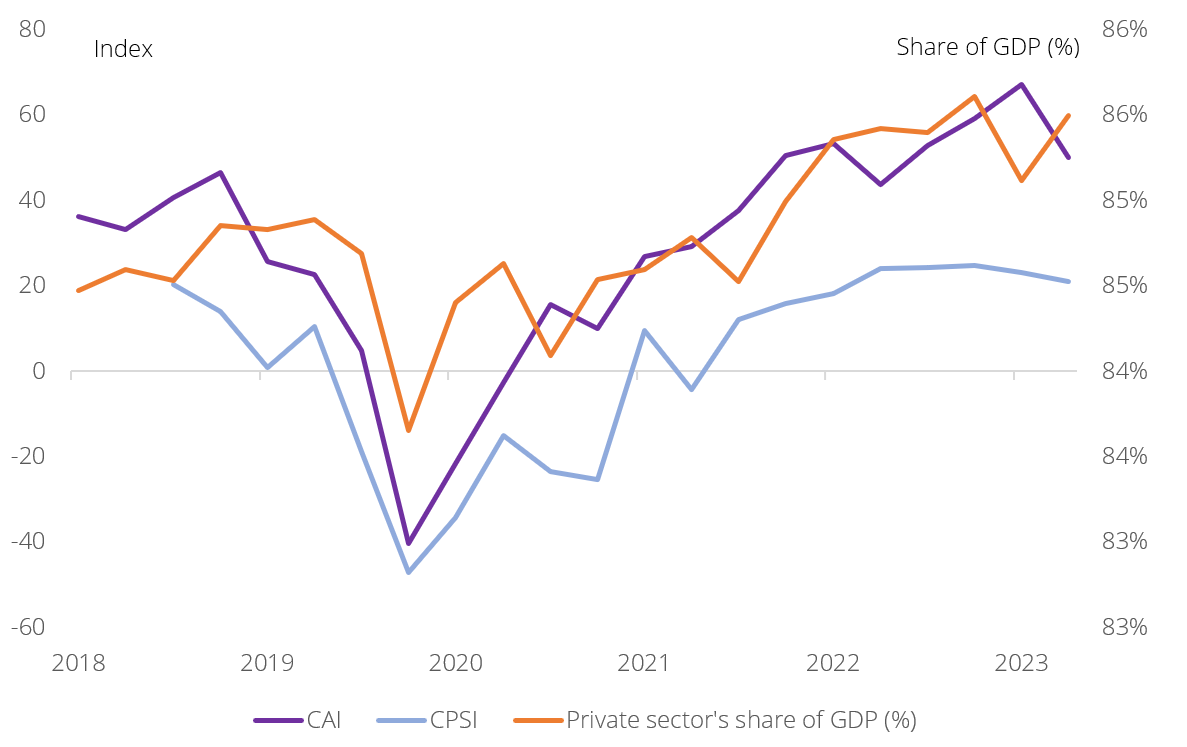

Notably, the contribution of the entire private sector to GDP has steadily increased since 2020. As Figure 2 shows, the upturn correlates with the RICS Construction Activity Index (CAI). This contribution also contrasts with figures from other markets, where public spending has been the main driver of the construction sector.

However, as the inclusion of the Commercial Property Sentiment Index (CPSI) in Figure 2 also shows, the confidence boost in the commercial property sector has not been as strong as that seen in construction

Figure 1: Construction Activity Index (CAI) by subsector and expectations. Source: RICS GCM, Q1 2024

Figure 2: RICS indices compared with private sector’s share of GDP in India. Source: World Bank and RICS

Workforce affected by lower participation and productivity

India has now surpassed China as the world’s most populous nation, and the median age in the former is 28 – compared to 39 in the latter – indicating considerable demographic potential. However, studies also show that the available labour this represents has not been fully capitalised on. Recent research from the IMF indicates that the contribution of this demographic dividend to Indian economic growth is relatively small.

Limited participation in the labour force by women could be a contributing factor. According to World Bank estimates in 2023, the labour force participation rate for women in the 15+ age group in India was only 33%, a figure considerably lower than the 57% of the US and 61% of China. The overall participation rate in the labour force in India was just below 55% in 2023, compared to 66% in China. However, if industrialisation and urbanisation in India continue to follow recent trends, we expect to see a steady increase in this metric.

Intertwined with this is the issue of low productivity: many Indian workers do not have access to education or training or incentives to upskill, especially in the construction industry, as highlighted by the IMF. Low labour force participation exacerbates this problem as households have less disposable income, suppressing the potential demand for products and thus meaning there is less reason for factories to scale up. The consequent automation would have encouraged people to train in the use of new technology; without it there is less sense in them gaining such skills, so the potential productivity of the population is lower. COVID-19 also disrupted progress in productivity, especially in the industrial sector.

The World Bank South Asia development update for April 2024 found that labour productivity growth in India surged between 2010 and 2019 but remained stagnant after 2020; indeed, it shows labour productivity in the Indian construction industry continues to be low, with limited progress towards the global productivity average. Although a more skilled workforce may help redress this, 70% of the respondents to the latest RICS GCM in India identified skill shortages as a hurdle for construction activities, making it the highest-ranking issue in the sector.

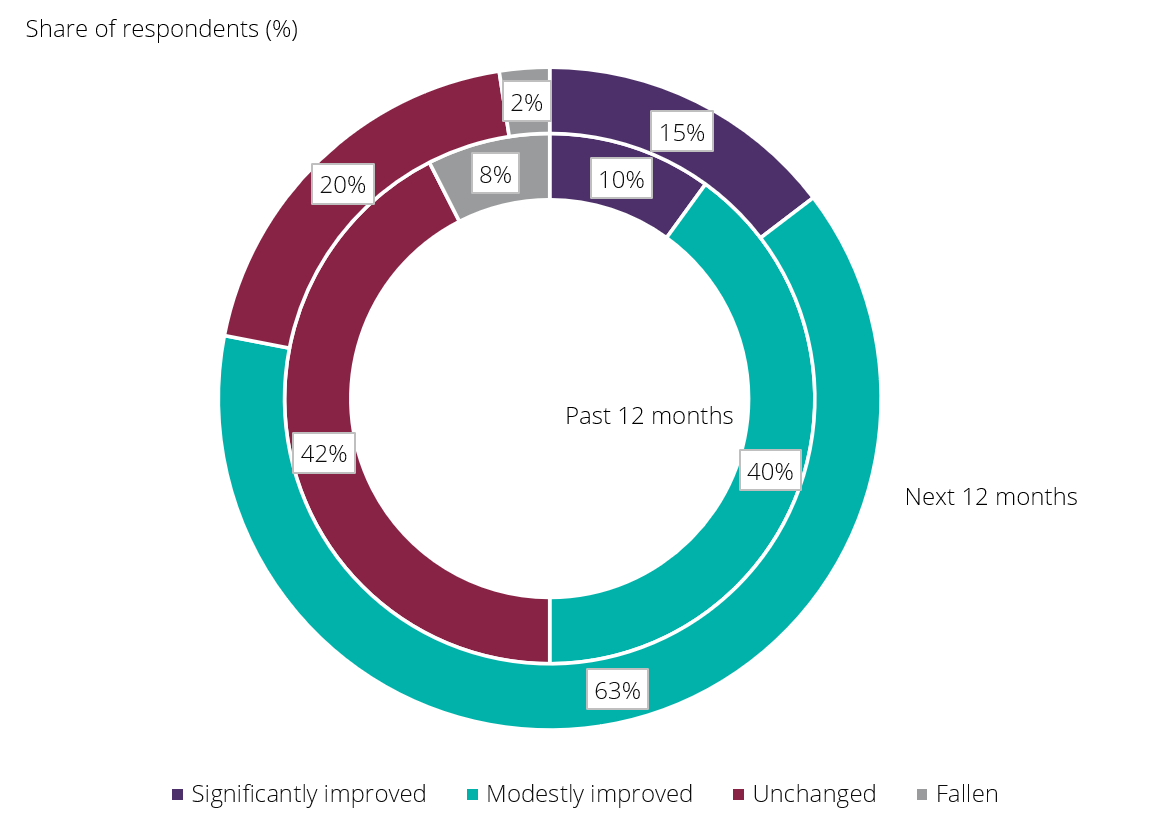

Reassuringly, RICS’ Construction activity report 2024 anticipates improvement. Figure 3 shows 78% of respondents to the RICS survey expect to see either modest or significant productivity improvements in India in the next 12 months, whereas only 44% anticipate such improvements on a global basis.

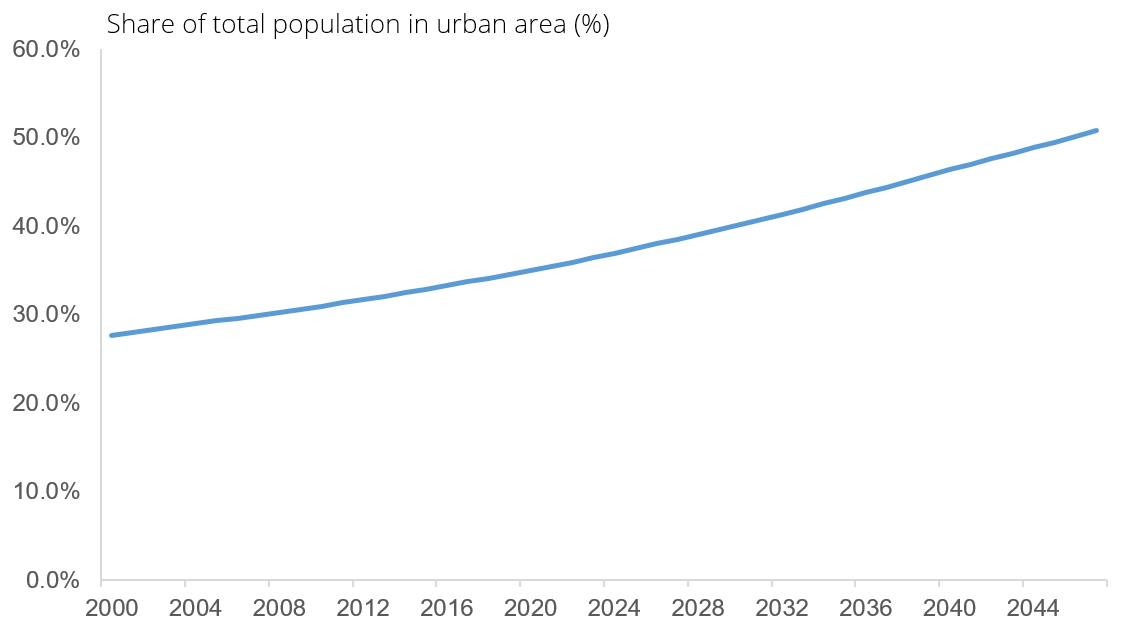

The trend of urban population growth is another relevant factor as it directly influences demand for residential and commercial properties. As Figure 4 shows, the proportion of India’s population living in urban areas is expected to increase steadily, rising from 36% in 2023 to 50% in 2047. This will generate robust demand for housing, which will in turn support the construction industry.

Figure 3: Perceptions of construction labour productivity in India for 12 months up to and after Q3 2023. Source: RICS Construction activity report 2024

Figure 4: Proportion of India’s total population living in urban areas, projected to 2047. Source: World Bank and Knight Frank estimates

Structural reform can help fulfil economic potential

The overall market sentiment about India's real-estate sector is positive. In the short term, growth potential is likely to be boosted by macroeconomic factors such as a robust domestic economy and external demand. Therefore, we expect the bullish trend in the building sector to be maintained, with continued infrastructure spending from the new government.

Long-term prospects to consider, meanwhile, include the continued growth of foreign trade and investment, efforts to improve low labour force participation rates – especially among women – and the policy drive to increase labour productivity. Structural reforms are projected to promote more balanced and sustainable growth – not just in the real-estate sector, but in the wider economy as well.