Anil Sawhney, Simon Rubinsohn, and Donglai Luo

1. Introduction

Compared to other industries that have seen substantial advancements in digitalisation and automation, the construction industry's productivity has been trailing behind. In 2023, we released the first edition of RICS’ Construction productivity report, in which we presented sentiment-based answers to broad questions about productivity improvement and development in the construction industry.

The 2023 edition illustrated how productivity trends and measurement frequency vary across geographical regions. It also pointed to a somewhat pessimistic view of productivity growth, with only 9% of respondents globally expecting an increase in productivity in the following 12 months. We aim to verify this observation in this 2024 report.

2. Survey

The sector has always been marred by the absence of a universal definition for construction productivity across various markets. This issue was also flagged in the RICS Construction productivity report 2023. Obviously, this complicates a meaningful global analysis and discussion, so we introduced a survey question to address this issue.

Like our previous study, it is also crucial to understand the factors that influence construction productivity, such as construction materials, skilled workforce, technology adoption, and the use of digital tools. Understanding these elements can guide the sector towards effective productivity improvement.

Based on these considerations, we modified the productivity-related questions included in the third quarter of RICS’ Global Construction Monitor survey 2023 (Q3 GCM 2023).

Specifically, contributors were asked to share their thoughts on six aspects of productivity in construction:

1. How is worker productivity defined in your company?

- Output per worker hour

- Productive worker time per total worker time

- Value of work completed per worker hours

- Value of work completed per worker costs

- Earned value over the actual cost

- Earned hours over the actual hours

- Worker hours per functional unit of the asset

2. Do you use industry benchmarks to compare worker productivity in your business?

- No

- Yes

3. How often do you measure labour productivity in your construction business?

- Weekly

- Monthly

- Quarterly

- Less frequently

- Never

4. Has labour productivity increased in your business over the past 12 months?

- Yes, significantly

- Yes, modestly

- No, it has remained unchanged

- No, it has fallen

- Don't know

5. Do you expect labour productivity to increase in your business over the next 12 months?

- Yes, significantly

- Yes, modestly

- No, expected to remain unchanged

- No, expected to fall

- Don't know

6. Rate the following factors impacting worker productivity in your business (high impact, moderate impact, low impact).

- Greater investment in automation

- Greater investment in data/digitisation

- Rationalisation of the structure of the industry through mergers and acquisitions (M&A)

- Increased focus on offsite construction

- Improved procurement and supply chain management

- Upskilling the workforce

- Drawing on materials innovation

- Not sure

3. Findings

Responses from the online survey were analysed using a spreadsheet tool. The results are presented at the global level and in five regions (the United Kingdom and Ireland (UK&I), the Middle East and Africa (MEA), Asia Pacific (APAC), Europe, and the Americas). Findings from the analysis are presented below.

3.1 Definition of construction productivity

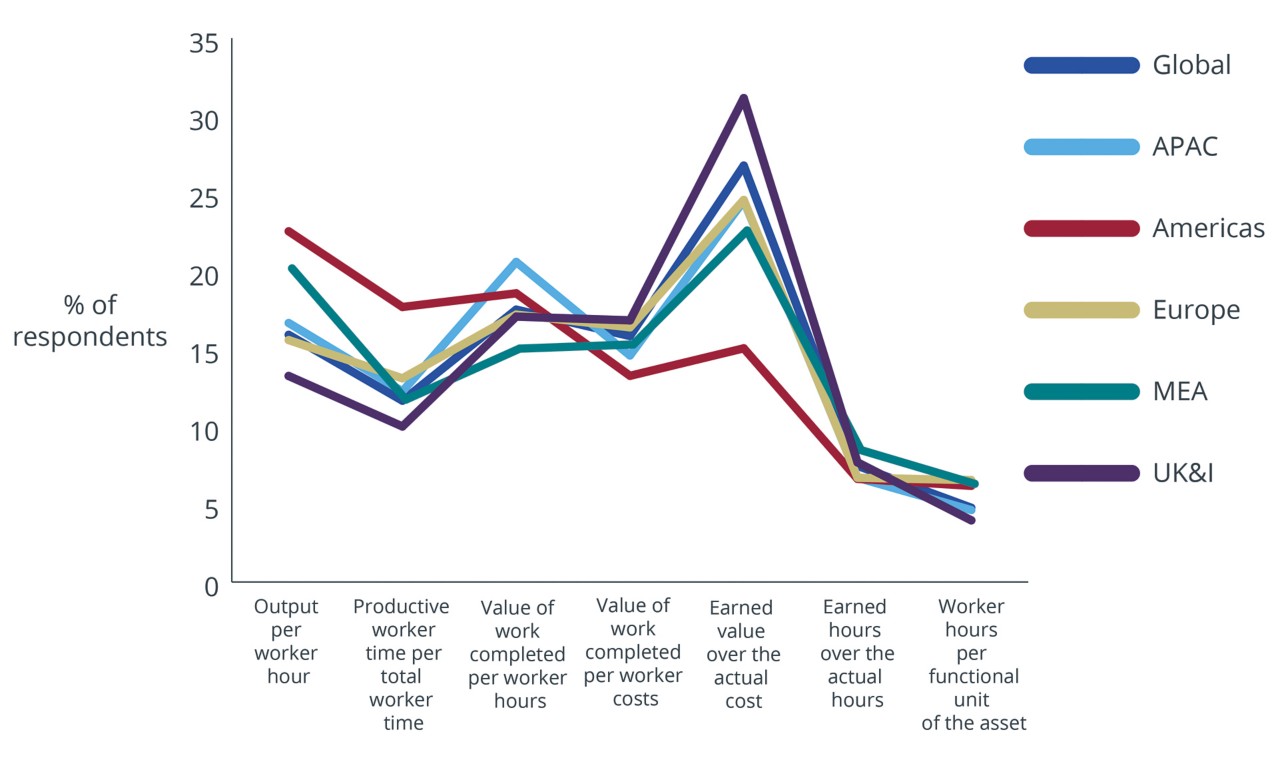

Globally, the most preferred definition of labour productivity is ‘earned value over the actual cost’, accounting for 26.8% of all respondents. However, there are regional discrepancies, as shown in Figure 1. Notably, ‘output per worker hour’ is the most accepted definition in the Americas. This option is also well received in the MEA, ranking as the region's second most popular definition of labour productivity. With more emphasis on the value of the output rather than the actual output, ‘value of work completed per worker hours’ is used comparatively more often in APAC except for ‘earned value over the actual cost’, which is the first choice for one in five respondents in the region. These findings explain the regional variations in defining labour productivity within the construction sector. Using various definitions means measuring different inputs, which increases the difficulty of comparing and benchmarking. This helps dispel some of the ambiguity noted in previous research regarding the definition of productivity.

3.2 Measurement frequency

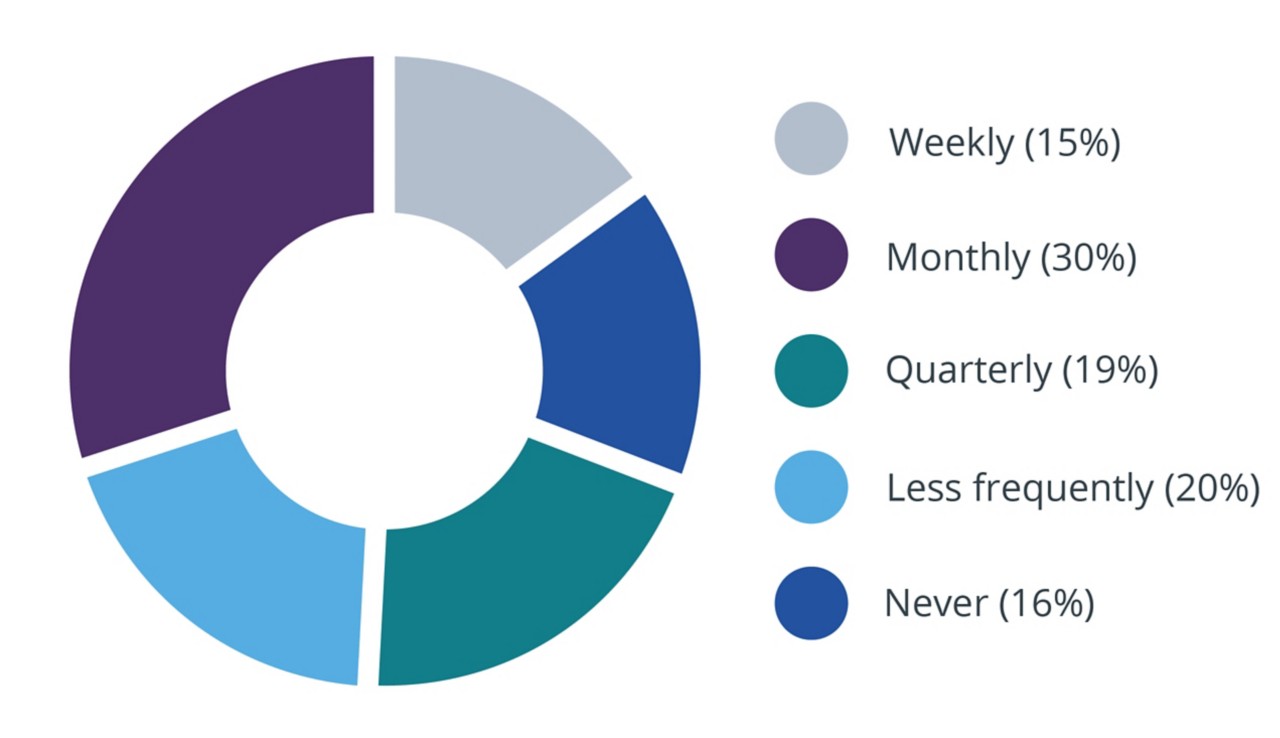

At the aggregate level, 30% of all respondents reported measuring productivity performance monthly, as depicted in Figure 2. Despite more responses from the UK&I, similar distributions are seen at a regional level in Figure 3. In the UK&I, however, around 22% of the respondents claim they never measure labour productivity, the highest among all regions, which could be due to a larger sample. On the other hand, the MEA has the highest proportion of people measuring labour productivity weekly. Correspondingly, the MEA and UK&I have the highest and lowest relative importance index (RII) performance, respectively (see Table 1).

Rank |

Region |

Frequency of productivity measurement (RII) (a higher RII means productivity is measured more frequently) |

1 |

MEA |

0.679 |

2 |

Americas |

0.653 |

3 |

APAC |

0.635 |

4 |

Europe |

0.608 |

5 |

UKI |

0.587 |

Table 1: Ranking of regions by the frequency of measurement

3.3 The past 12 months and the next 12 months

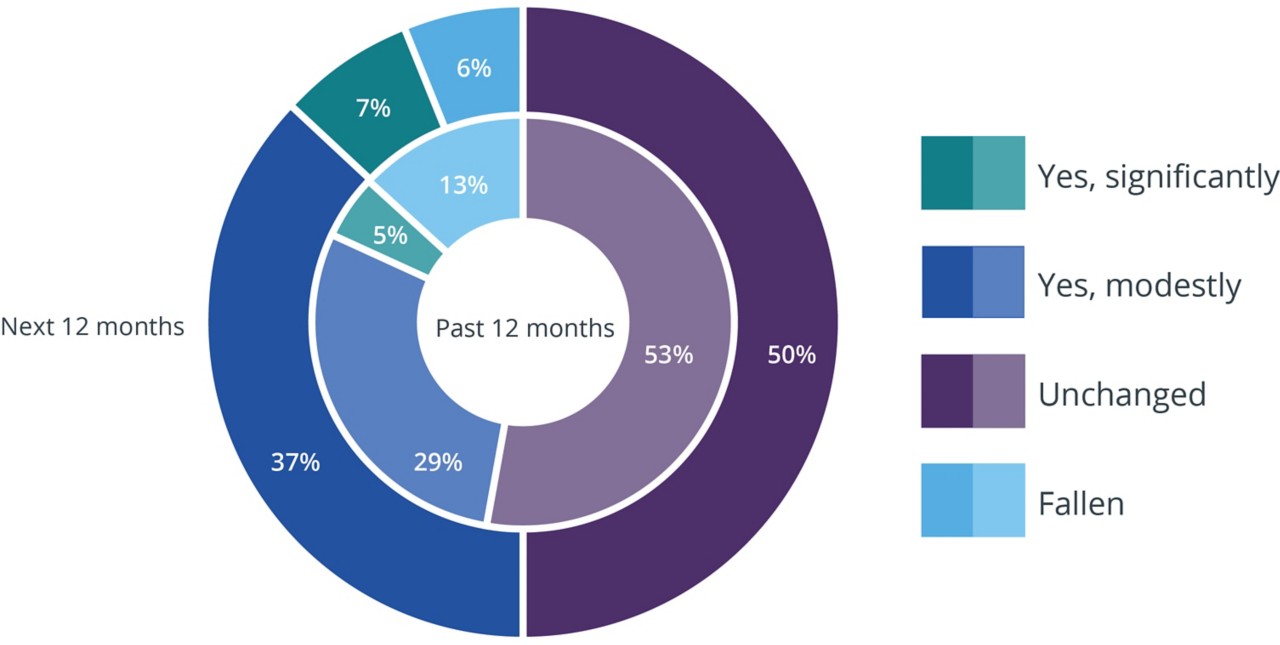

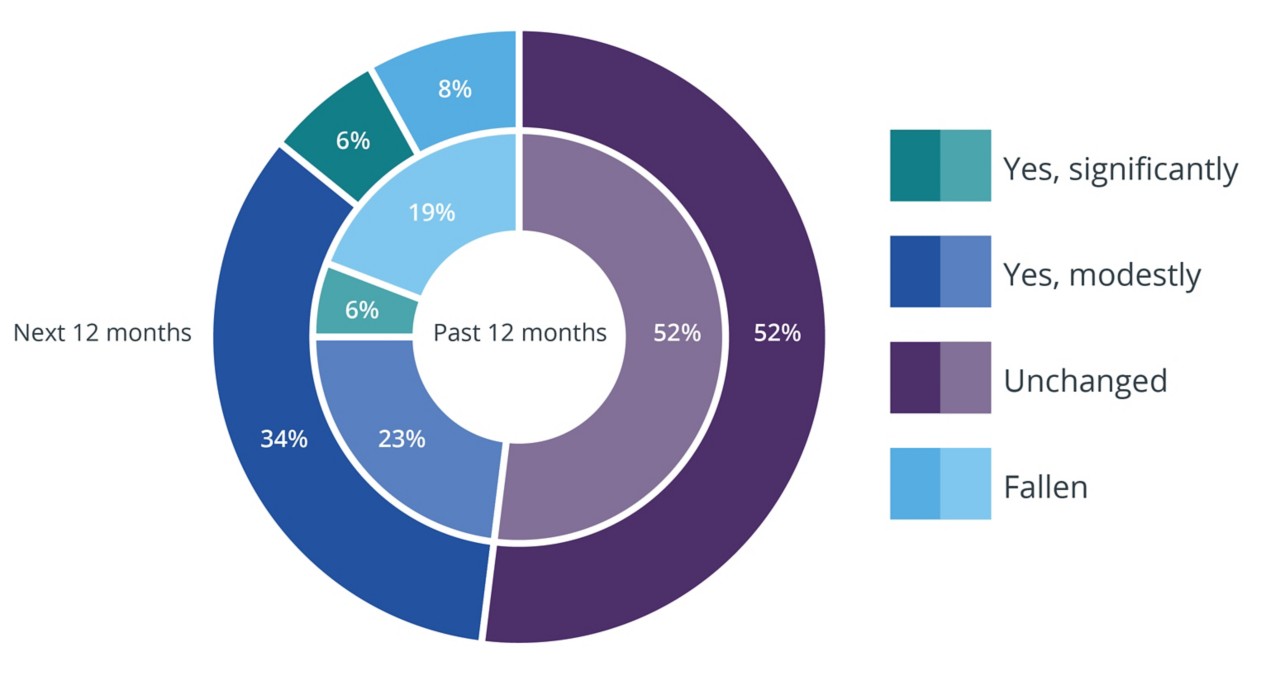

In the third question, respondents were asked about the trend in labour productivity both over the past 12 months and expectations for the next 12 months. Figure 4 shows the responses to both questions. Thirty-four per cent of respondents saw increased productivity in the last 12 months, while 53% did not see any change in productivity. Forty-four per cent of respondents expect labour productivity to increase over the next 12 months, while 50% expect labour productivity to remain stagnant. Respondents are generally optimistic about the outlook for labour productivity.

On a regional basis, this optimistic scenario is more or less consistent. Figure 5 shows construction productivity in the UK&I for the past 12 months and the next 12 months. There is an upward trend in productivity when comparing responses for the past 12 months with the next 12 months. However, compared to other parts of the world, the UK&I has more respondents, indicating a pause in labour productivity improvement for the past 12 months and the 12-month outlook.

Figure 6 shows labour productivity in the MEA for the past 12 months and the next 12 months. There are signs showing productivity improvements, with a larger proportion of responses indicating increasing productivity, significant or modest, in the next 12 months as opposed to the past 12 months.

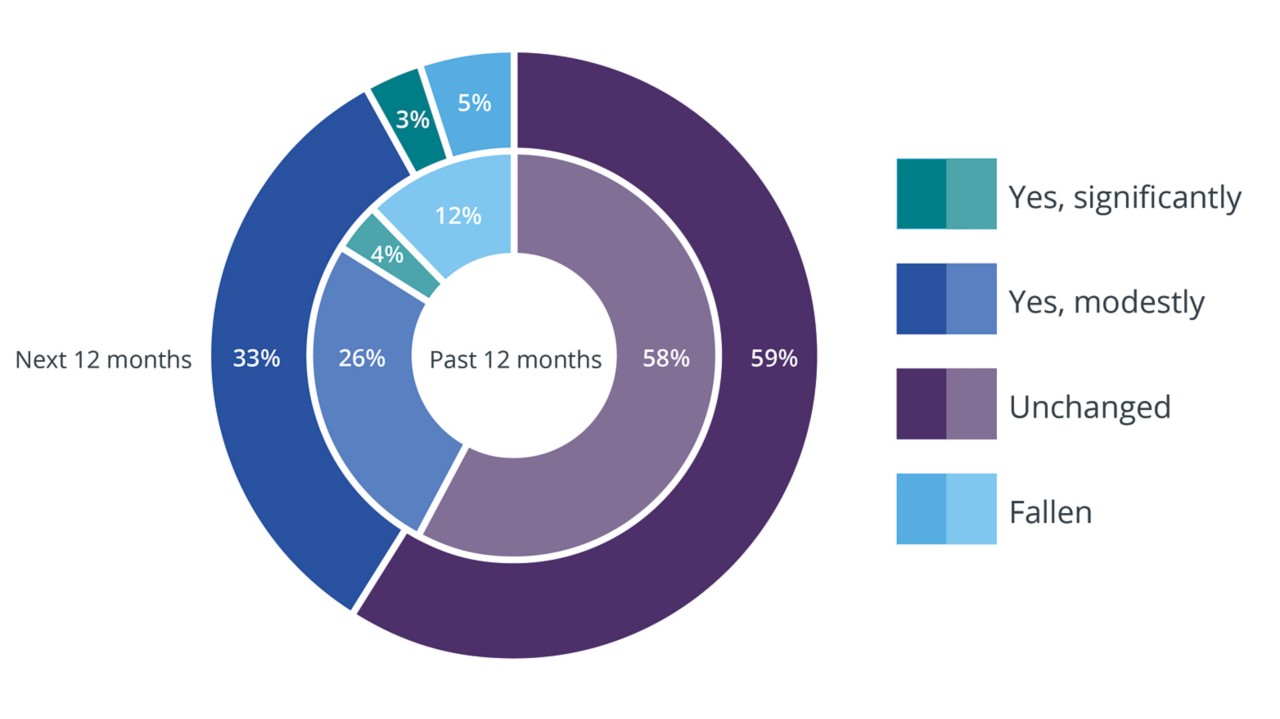

Europe also has growing optimism, with a larger share of respondents indicating increasing productivity compared to the past 12 months (see Figure 7).

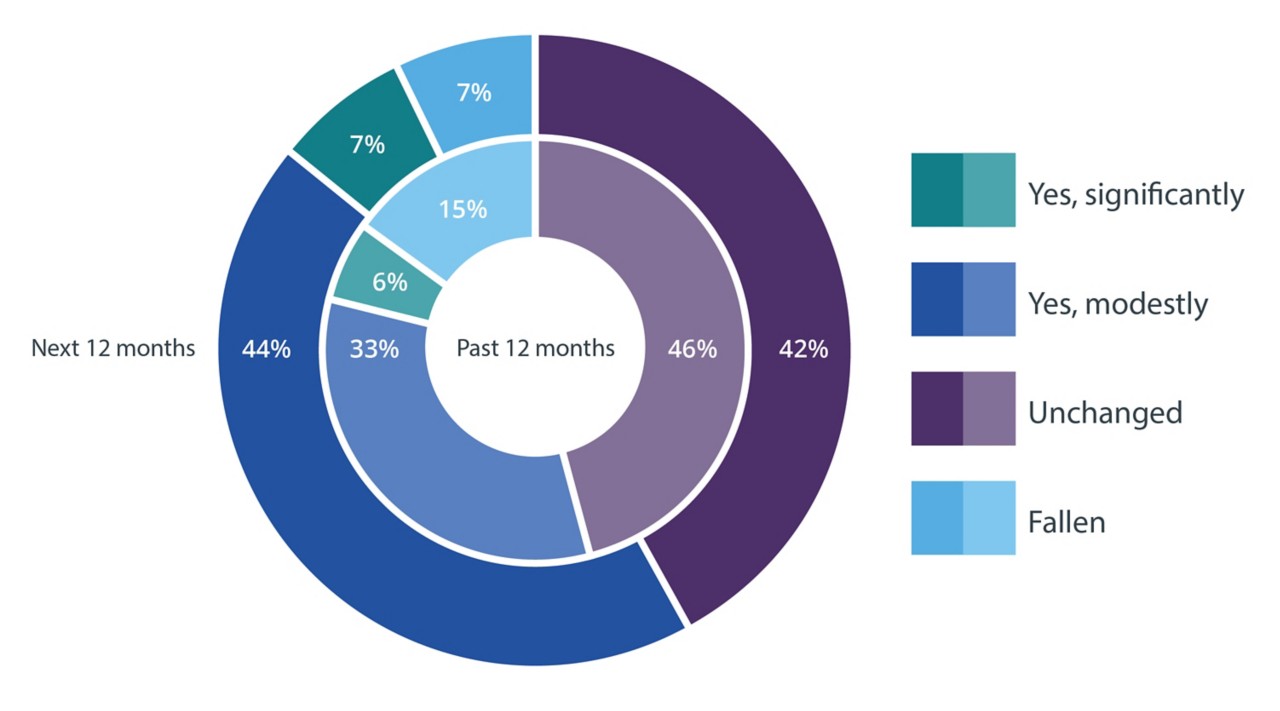

Figure 8 provides the construction productivity responses of the Americas. Twenty-nine per cent of contributors saw an increase in construction productivity over the preceding 12 months, while 40% expected productivity to increase in the upcoming 12 months. Adding to the upbeat outlook, only 8% of respondents expect productivity to fall, while only 19% saw decreasing productivity in the past 12 months.

Similarly, in APAC, more than half of respondents expressed optimistic views on the productivity trend for the next 12 months.

3.4 Interventions to increase productivity

In the last set of questions, respondents were asked to rate the impact of different factors on labour productivity. As shown in Table 2, overall, the availability of skilled workers ranks the highest in terms of its impact on productivity, with 46% of respondents confirming its importance globally. Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum, 48% deem construction equipment and tools to have a low impact.

|

% |

||

Productivity interventions |

High impact |

Moderate impact |

Low impact |

Construction equipment and tools |

20 |

32 |

48 |

Materials, including prefabricated modules |

25 |

32 |

44 |

Construction documentation |

26 |

43 |

32 |

Site supervision and coordination |

31 |

38 |

32 |

Availability of skilled workers |

46 |

32 |

22 |

Changes and variations |

35 |

42 |

23 |

Supply chain |

33 |

42 |

25 |

Site safety and well-being |

20 |

42 |

38 |

Procurement route and contracting model |

29 |

45 |

26 |

Scheduling, sequencing and coordination |

34 |

42 |

24 |

Table 2: Ranking of productivity interventions globally

Looking closely at the regional ratings of the factors (see Table 3), the availability of skilled workers continues to show a high impact in all regions. Besides this, ’site supervision and coordination’ is also a key factor boosting productivity in the MEA, Europe and the Americas. Geographically, the MEA region features more high-impact factors than the rest of the world, which suggests more potential opportunities for labour productivity improvements in the region.

Productivity interventions |

Ranking |

|||||

APAC |

Americas |

Europe |

MEA |

UK&I |

Global |

|

Construction equipment and tools |

Moderate |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Materials, including prefabricated modules |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Construction documentation |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Low |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Site supervision and coordination |

Moderate |

High |

High |

High |

Low |

Moderate |

Availability of skilled workers |

High |

High |

High |

High |

High |

High |

Changes and variations |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

High |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Supply chain |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

High |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Site safety and well-being |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Low |

Moderate |

Procurement route and contracting model |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Scheduling, sequencing and coordination |

Moderate |

High |

Moderate |

High |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Table 3: Ranking of productivity interventions by region

4. Conclusions

Labour productivity in the construction sector has been reported to be among the lowest across industry sectors (see RICS Construction productivity report 2023). As part of the Q3 GCM 2023 survey, questions were asked to investigate the intricacies of this issue. In this analysis, we have compared and identified discrepancies in the definition of productivity across different regions, paving the way to a deeper understanding of the construction productivity issue. The data show regional variations in the frequencies of measurement of labour productivity, where we see more regular measurement in the MEA. Our results also reveal a mixed picture regarding productivity improvements across regions. Globally, the percentage for positive expectation of productivity improvement increased to 44%, compared to 34% in 2023, with respondents stating an increase in productivity in the preceding 12 months. The availability of skilled labour stands out, with the highest impact indicated across all regions.

Term |

Definition |

Output per worker hour

|

Direct measurement of construction productivity calculated by dividing the units of work completed by the number of hours worked. |

Productive worker time per total worker time |

Direct construction productivity measurement by tracking non-value-adding time. This method incorporates the efficiency of construction work. |

Value of work completed per worker hours |

The value of work completed is determined by applying the percentage of physical progress achieved to the general contract or purchase order value, including any approved changes. Productivity is determined by dividing the value of work completed by the actual worker hours expended in completing the work. |

Value of work completed per worker costs |

The value of work completed (explained under the definition of ‘value of work completed per worker hours’) is divided by the actual worker costs expended in completing the work. |

Earned value over the actual cost |

Earned value (EV) is the measure of work performed, expressed in terms of the budget authorised for that work. Construction productivity is calculated by dividing the EV by the money spent to accomplish the progress. |

Earned hours over the actual hours |

EV is the measure of work performed, expressed in terms of the budget authorised for that work. Construction productivity is calculated by dividing the EV by the actual worker hours to accomplish the progress. |

Worker hours per functional unit of the asset |

A functional unit is a unit of measurement used to represent the prime use of an asset or part of an asset (e.g., per bed space, per house, per kilometre, per highway lane, or per square metre of retail area). Construction productivity is calculated as the hours to complete the selected functional unit. |

“As we navigate through the evolving landscape of the construction industry, the RICS Construction Productivity Report 2024 illuminates the path towards transformative productivity enhancements. This year's report not only underscores the pivotal role of digitalisation and skilled labour in catalysing growth but also offers a view of regional variations and the sentiment in the sector. The report states we should endeavour to redefine benchmarks and embrace innovation, ensuring a resilient and efficient future. As we forge ahead, this report serves as a testament to our industry's commitment to excellence and sustainable progress.”

James Garner BSc (Hons) FRICS RITTech MBCS

Global Head of Data, Insights & Analytics, Senior Director, Gleeds Cost Management Limited, RICS Construction PGP Member

“Productivity lies at the heart and soul of performance improvement. I hope this important report encourages the industry to think more deeply about productivity, about what it really means, about what really affects it, and how it can really be improved.”

Malcolm Horner BSc PhD CEng FICE FRSE Hon FRIAS, Whole Life Consultants Ltd, Emeritus Professor of Engineering Management, University of Dundee

Chairman

“Availability of skilled workers is one of the key challenges in the construction industry at present, and this is echoed in this report - ranking the highest in terms of its impact on productivity.”

Ameya Gumaste FRICS

Executive Director & Country Head, India, Linesight