Tony Mulhall, Senior Specialist, RICS

Growing inequality is politically destabilising – lack of access to affordable housing contributes to this.

Earlier this week RICS hosted Martin Wolf, Chief Economics Commentator at the Financial Times who presented a lecture entitled ‘The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism’ the title of his most recent book. A former chief economist at the World Bank, he has published numerous books on economic impacts on society and provides trenchant commentary on day to day economic affairs in the FT. This RICS/University of Oxford/King’s Foundation joint annual public lecture is part of an outreach programme to bring the views of thought-provoking speakers in our sector to a wider audience.

His increasing concern is that in our developed political economies, market capitalism and liberal democracy are in a fragile state. “Market capitalism rests on ideals of free labour, individual effort, reward for merit and the rule of law. Democracy rests on ideals of free discussion and debate among citizens when making those laws.” Arguing that democracy and capitalism are complementary opposites, both market capitalism and liberal democracy need to be functioning properly to enable everyone to enjoy the benefits of that society. As our economies have evolved, the benefits of contemporary societies are increasingly concentrated in a few hands. With the advent of AI he foresees that trend continuing while acknowledging the possibility of more widespread benefits. The worrying result: large groups of people may feel unable to attain what were normal expectations in the past. They may be persuaded by charismatic political figures that the gradual suspension of democratic rights will help restore past glories. This happened with the growth of Fascism accompanied by catastrophic consequences for Europe in the 1930s.

Satisfying the centre ground

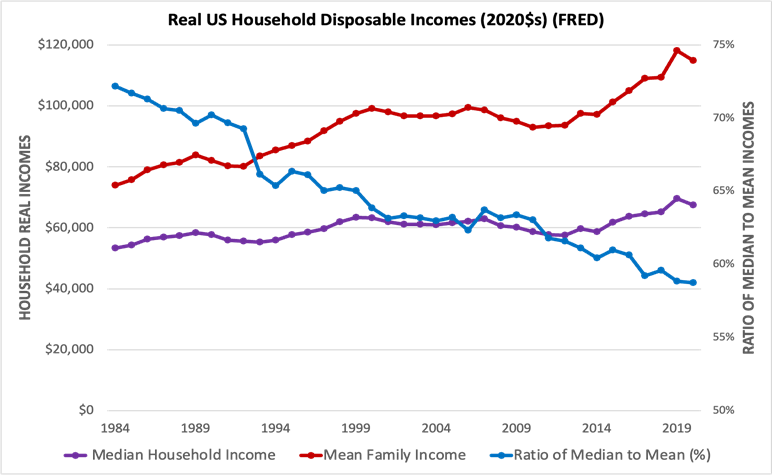

He particularly identified the importance of being able to meet the aspirations of the large centre ground of the population – those on median incomes. Illustrating this by looking at the ratio of Mean Family Incomes to Median Family Incomes in the United States from 1984-2019 he observed the gap that has opened up between higher earning and lower earning families. Mean family income is a simple average. The red line indicates its long-term increase. But it tells us nothing about the extremities of the income distribution – the extreme high and low income families.

Martin Wolf, Financial Times

Helping to clarify this is the purple line showing the trend in median incomes – the income level that most families earn. The increase is much more gradual and the gap in 2019 much wider than in 1984. But even more revealing is the ratio of median to mean indicating that median incomes have declined from approx. 72% in 1984 to approx. 58% of average household incomes in 2019. These figures are reflected in the responses of dissatisfaction from this large group of median income earners, at a time when aggregate GDP figures may indicate certain economic sectors are doing well.

Rising inequality, de-industrialisation, falling growth

Wolf attributes the economic source of these problems to “rising inequality, de-industrialisation, and falling growth”. “Large rises in inequality and the deteriorating prospects of the old “respectable” working and middle classes in core democracies have been weakening the foundations of democracy.” “Fear of downward mobility has created “status anxiety” and cynicism. These have then been diverted by right-wing propagandists into cultural and racial resentments, especially in ethnically diverse societies. Mass immigration is a potent weapon in such politics.”

This was a strong message about the risks of inequality becoming so embedded in our political system that our democratic processes prove powerless to address. Persistent failure of successive democratically elected governments to deal with inequality may give rise to the feeling among disadvantaged people that the system is structurally biased against them.

One of the sources of these inequalities - housing - is in our sector. The inability of the sixth largest economy in the world to build enough housing to affordably house its population is a major failure. Even with the latest government proposals to address this problem, few people in the sector believe the government will come close to meeting its housing targets in 5 years.

RICS hosts numerous foreign government delegations who come to discuss how they can house their populations affordably. A lack of adequate housing for rapidly growing populations is potentially extremely de-stabilising for governments in these countries. But it doesn't matter whether they come from developing or developed countries, the issue always turns to access to land.

Land value tax

Have we struck the right balance between land as a private asset and land as a public good in the UK? Irs there something unique about land and where it is positioned in our political economy that makes it particularly problematic when used as a factor of production in housing?

On this subject Wolf declared himself a Georgist meaning he subscribes to the ideas of US nineteenth century political economist Henry George who advocated taxing the value of land. He has long been a supporter of taxing land value and said “such a tax would be economically efficient and morally just. But it has been politically impossible: the landowning interest, which now includes a large part of the population as owner-occupiers, has been too strong. Now that western politicians are struggling with low growth, stressed public finances, high inequality, intergenerational tensions and an unstable financial system, they need to consider such a fundamental change in what is taxed.”

At various levels RICS through our members is worrying through these issues. In responding to the Government's latest consultation 'Land Use Framework' we will have an opportunity to again consider the role of land from an agricultural perspective. All views are welcome for consideration.

The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism By Martin Wolf | New and Used | 9780141985831 | World of Books