Introduction

BTY Group is a leading quantity surveying, project management and construction advisory consultancy established in 1978. The firm is a longstanding member of RICS with a diverse staff of more than 160 professionals, including chartered surveyors, project managers and engineers.

The Canadian government has identified decarbonization as an immediate and sustained priority as part of its environmental, social and governance (ESG) objectives. Canada’s ESG goals include closing the infrastructure gap in urban, rural and remote communities, and reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. The most severe infrastructure deficiencies exist in Indigenous communities across Canada. Achieving these objectives will require the support of all provinces and territories, and every community and industry.

The infrastructure gap comprises:

- severe overcrowding in dilapidated housing and education facilities

- boil water advisories

- a lack of adequate waste treatment systems and all-season road access

- a dependence on fossil fuels for energy and heating due to a lack of renewable alternatives and

- a lack of high-speed internet connectivity.

The path to these objectives also needs to be equitably shared between Canada’s Indigenous and Non-Indigenous peoples. Progress on a just energy transition, access to critical minerals and climate-resilient local economies are not possible without first addressing the dire infrastructure needs of all Indigenous communities.

Canada’s Indigenous peoples are disproportionately impacted by flooding, wildfires, and droughts – challenges which are increasing in severity due to climate change. Because of this, the project was designed to be First Nations-led.

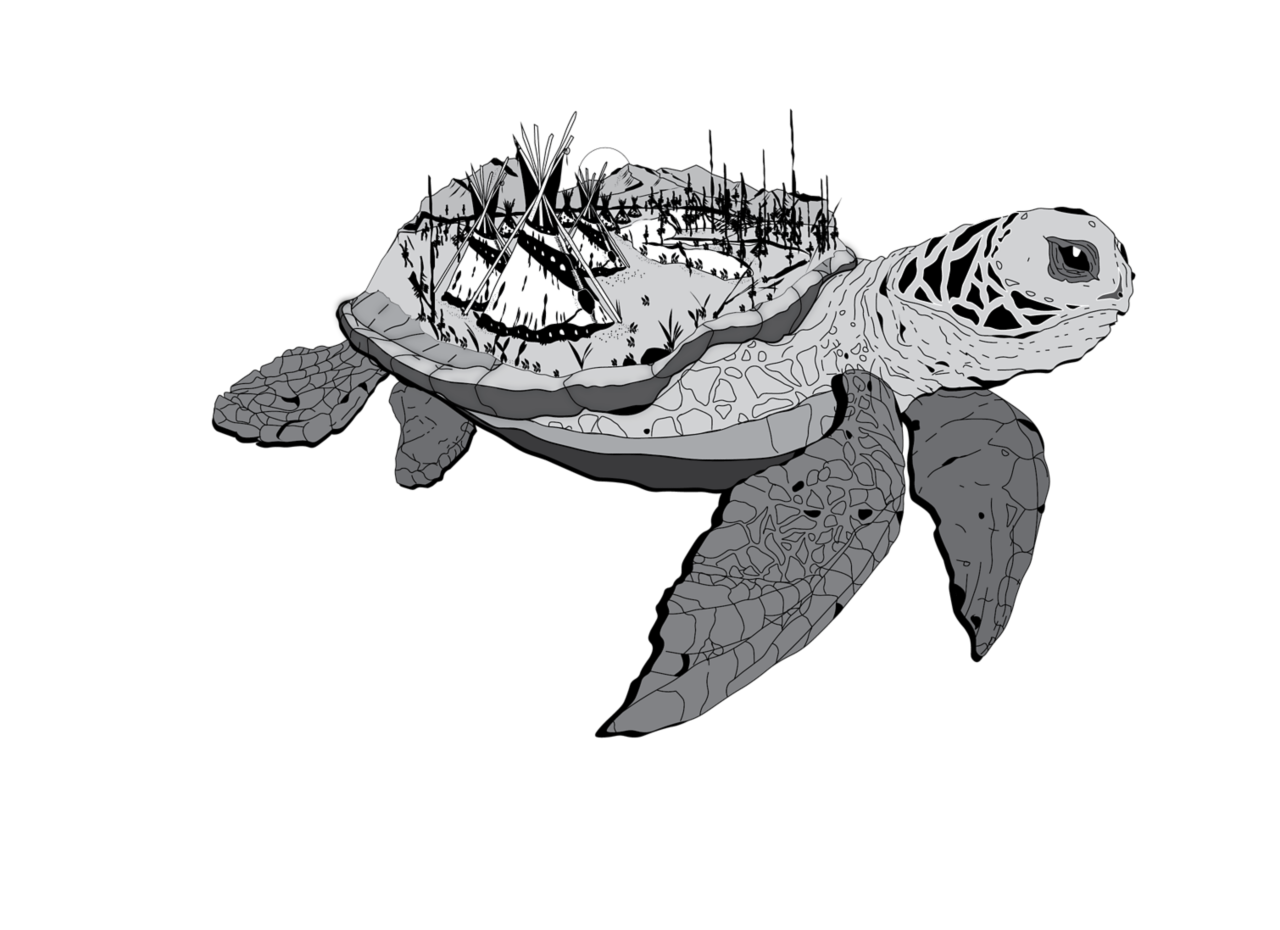

The reports also featured artwork of the built environment from an Indigenous perspective through illustrations by Dene artist Darren Yallee. A selection of these is included in this case study.

Project overview

BTY was engaged by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), with the support of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), to lead the first-ever national study of combined infrastructure and housing needs for more than 600 First Nations.

The project had two phases.

- Phase one included a funding proposal to the government of Canada and a comprehensive cost report, which was completed in November 2022.

- Phase two included a program prioritization and implementation plan, which was completed in August 2023.

The research included analyzing data from hundreds of First Nations across Canada, a geographic area of approximately 9.98m km², and comprised a variety of assets required to improve long-standing socioeconomic inequities.

Challenges

The challenges we encountered came from this initiative being the first of its kind in Canada. It was critical for the study to be led by the First Nations, involving deep discussions on what the infrastructure priorities are and who gets to decide them.

Technical challenges on this project included managing a large volume of historic cost data from different sources, in different formats and from different time periods. Our team also provided input to help navigate key economic challenges including record-high inflation and how a mandate of this size and scope could be delivered. Stakeholder engagement challenges included factoring in inputs from hundreds of communities, public sector leaders and industry partners.

BTY’s methodology included regional and zonal factors impacting costs and implementation due to remoteness and accessibility issues. Most First Nations are in rural or remote areas. Their communities are found on islands, in isolated coastal villages, in mountain valleys, and in the Arctic and Subarctic as well as in urban reserves.

Figure 1 below captures the magnitude of what the study covered in terms of the total estimated capital and operating costs distributed across ten different asset categories.

Solutions

Resolving these challenges required collaboration and tailored solutions. While AFN and ISC provided a large volume of historic data for analysis, the data was in different formats that needed to be standardized for effective use and included gaps that needed to be addressed.

As the study’s main objective was to support a funding proposal to the Canadian government, financial constraints formed the core of our recommendations. We also applied the cost breakdown by region, zone and asset type to an integrated schedule and cash flow, which we mapped to demonstrate what would be required to effectively close the infrastructure gap by 2030.

This approach highlighted the inadequacy of the government’s current model of funding piecemeal projects as opposed to creating a unified and reliable funding mechanism. To highlight the changes necessary, we recommended:

- improving procurement practices to support greater innovation and competition

- leveraging the best procurement models based on the community’s needs and affordability factors

- incentivizing greater public-private-community partnering opportunities

- prioritizing capacity to increase First Nations’ workforce participation in construction and

- innovation in financing to access long-term capital solutions.

Stakeholder engagement was a cornerstone throughout our mandate. Equitably addressing the concerns of closing the infrastructure gap necessitated discussions with AFN to ensure the study captured First Nations’ needs.

Success factors

The core theme for the success of the study was the commitment to collaboration, ensuring the First Nations’ perspectives led the research process. We focused on bringing in multiple experts to provide an analysis of how Canada can implement the program with a focus on meeting ESG objectives.

Historic data and direct input from First Nations communities was also critical. We reviewed dozens of reports and other data to assess the disparity between First Nations infrastructure assets and the rest of Canada. Figure 2 below illustrates the scale of infrastructure investment required across Canada’s provinces and territories.

Outcomes and lessons learned

The AFN is extremely positive about the report’s breadth of scope, depth of analysis and value in validating a unified request for support from the Canadian government that is backed by construction industry expertise and private sector enterprise.

Findings from this project have been shared with First Nations chiefs and have been widely acknowledged for summarizing decades of data. They provide a cohesive and defendable rationale about the gravity of the infrastructure gap, the urgent need to act and the once in a generation opportunity to implement a national ESG-focused infrastructure program to unlock a low-carbon and prosperous future for some of the country’s most vulnerable populations.

Our reports set new best practices in quantity surveying and implementation planning to develop the first-ever national program that quantifies capital, operating and maintenance costs for the infrastructure needs of more than 600 First Nations. Although our mandate involved Canada’s First Peoples, the learnings are applicable to many regions where indigenous populations are facing an infrastructure gap.

Matthew A. George, Senior Policy Analyst – Infrastructure, Assembly of First Nations, summed up BTY Group’s contribution:

‘The report was the first of its kind to isolate infrastructure and housing costs by First Nations’ distance from an urban centre while capturing cost factors that differ for each First Nation according to their applicable Province or Territory.

The entire team should be commended for their commitment to producing this significant study, utilizing their expertise … and helping develop the first comprehensive account … of the infrastructure gap and the scale of long-term socioeconomic opportunities addressing it will unlock for First Nations and Canada.’

We created tools and resources to communicate the objectives and findings of the study to a variety of audiences, including presenting directly to hundreds of First Nations community leaders and collaborating with a variety of subject matter experts.

Some of the recommendations the study explores are captured in the list below to demonstrate the areas of insight our team contributed to.

Implementation objectives

- Enable First Nations to develop and administer community asset management plans.

- Develop reliable and sustainable long-term funding sources.

- Invest in First Nations’ capacity and human capital development.

- Address deficiencies backlog and fast-track shovel ready projects.

- Improve competitiveness of procuring and delivering First Nations infrastructure.

- Help Canada achieve its net-zero commitments through First Nations-led initiatives.

- Convene communities of practice with First Nations, industry and the public sector.

Conclusion

For the first time in Canada’s history, this mandate has delivered a fuller picture of the dire need for infrastructure investment for the country to fulfill its fiduciary commitments to its First Peoples, comply as a signatory of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and achieve its target for net zero emissions by 2050.

The study’s scale and complexity set a new precedent for meaningful collaboration and partnership-driven analysis and solutions, which are critical if Canada is to achieve its obligations of reconciliation with the First Nations, close the infrastructure gap and implement a viable path to a prosperous and equitable low-carbon future.